Introduction

In the last three months, there has been a 50% uptick in ransomware, with the Ryuk ransomware garnering the most attention after a string of high profile attacks that have been crippling companies. Last month it was reported that Ryuk hit UHS hospital networks with force, spreading across UHS healthcare facilities in the US from coast to coast. This well-orchestrated attack left many hospital workers without access to labs, radiology, and patient records, which led to workers having to resort to pen and paper to triage patients. Ryuk is currently attacking approximately 20 organizations a week, and this number will only expand due to its successes.

There are a number of factors that contribute to this success. These include its harnessing of other “toolkits” such as TrickBot and Emotet, and being quick to jump on newly-exposed vulnerabilities such as Zerologon. We also see that Ryuk has iterated since its earlier incarnations to evade detection and markedly improve the time it takes from execution to full encryption, making life increasingly difficult for organizations that cannot respond to threats at such speed.

In this post, we look at how Ryuk has evolved since 2018 and explore the improvements in encryption speed and evasion techniques that we see in Ryuk samples today. Along the way, we detail a method analysts can use to extract the Ryuk executable from memory and dump it to file for further inspection.

Ryuk Overview

When Ryuk ransomware burst onto the scene, it was initially believed that it was developed by the same threat actors who developed Hermes Ransomware. However, it was later discovered that Hermes was being sold on the black market, allowing cybercriminals to purchase the framework and convert it to what is known today as Ryuk.

The current waves of attacks have been known to use a combination of Emotet, Trickbot, and Ryuk. In recent weeks, the actors behind Ryuk have even been observed using ZeroLogon to extend their reach and broaden the delivery of their ransomware payloads. While the Ryuk payloads do not specifically contain the ZeroLogon functionality, the flaw is being leveraged at earlier stages in the attack chain. Attackers are able to use existing capabilities in Cobalt Strike and similar frameworks to achieve the privilege escalation. It is quickly becoming clear that ZeroLogon will become a staple in the attackers’ collective “toolbelt”.

Reversing and Comparing Ryuk 2018 and 2020

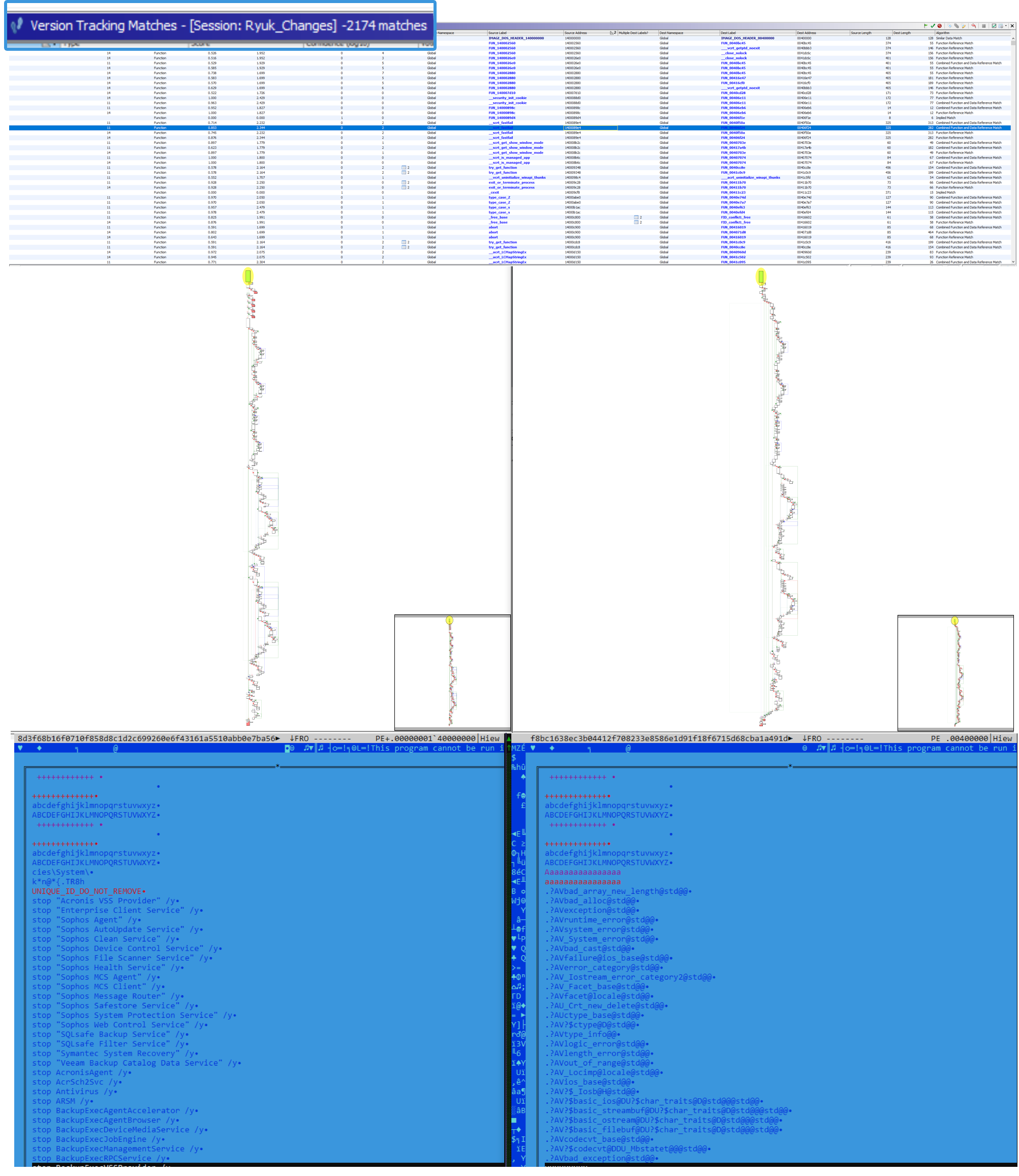

There are many tools in the reversing ecosystem for diffing binaries like Bindiff, but a fast tool when comparing binaries I find most useful is Ghidra’s version tracking to check for comparisons between binary files.

If we compare an earlier version of Ryuk with the latest version, we can note some interesting changes. In the most recent version, Ryuk obfuscates its hardcoded strings to become more difficult for AV vendors to detect:

Ryuk 2020 also copies itself to increase the speed of encryption, which we discuss in detail below.

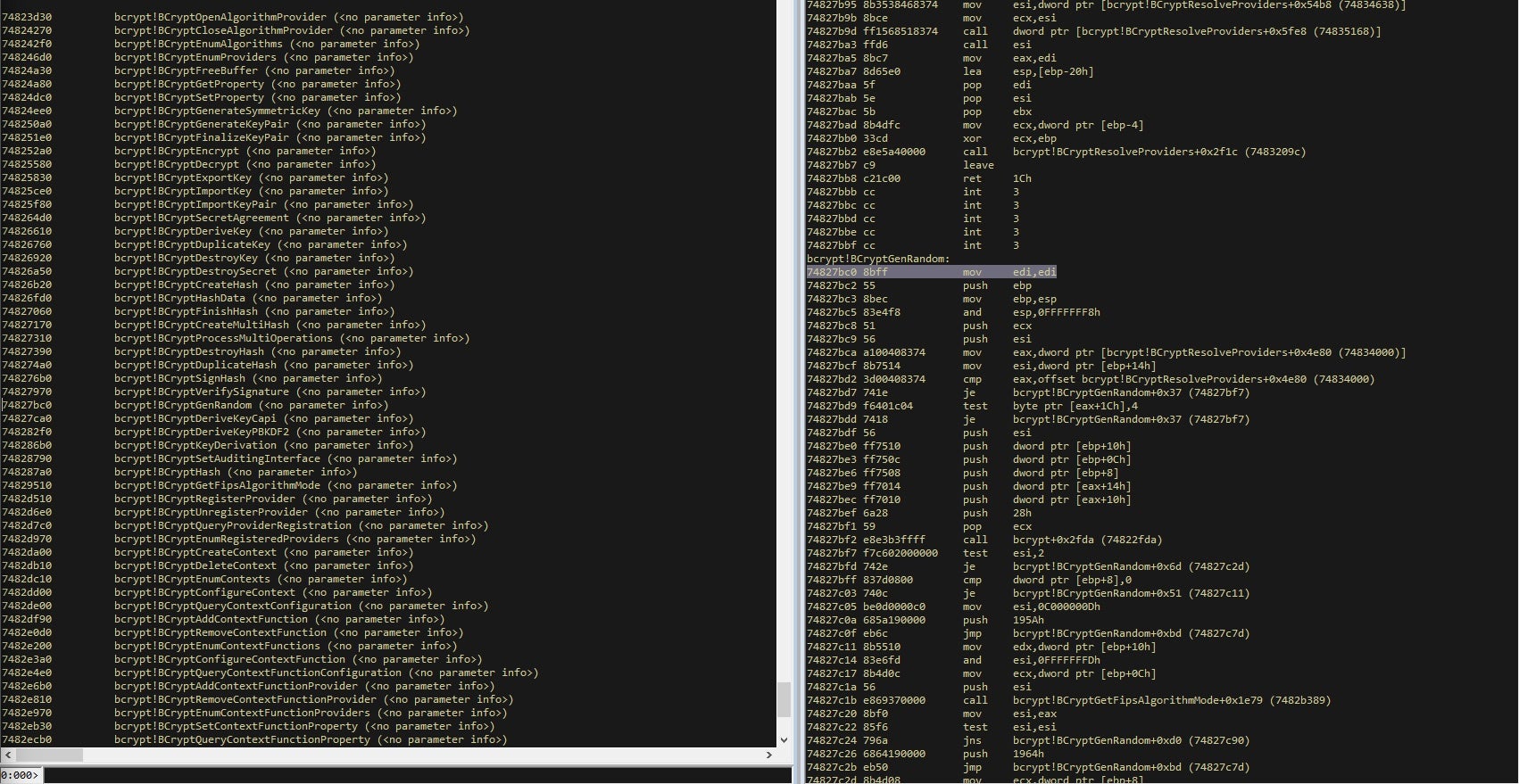

The ransomware uses RSA and AES to encrypt files with extension .ryk, creating a new thread for each file it encrypts. Ryuk also uses the CryptGenRandom API, which fills the buffer with random bytes to generate a data encryption key.

Since this API has been deprecated, I would expect the actors to change this in a future version of the ransomware, perhaps to the newer Cryptography API: Next Generation (CNG), which provides a new API BCryptGenRandom to achieve the same result.

A significant difference between the earlier Ryuk binary and our recent sample is the time it takes to fully encrypt the local disk. The 2018 binary takes close to one hour to encrypt the local disk, while the 2020 version takes less than 10 minutes.

The increased encryption speed of the newer Ryuk variant places an extra burden on enterprise security efforts. The reaction time to detect, mitigate, and eradicate Ryuk before major damage is done is significantly limited, and many organizations have been unable to contain the ransomware in time. This occurred in UHS networks and required hospital staffers to shut down computer systems immediately to prevent further machines becoming infected by Ryuk.

Diving Deeper into Ryuk 2020

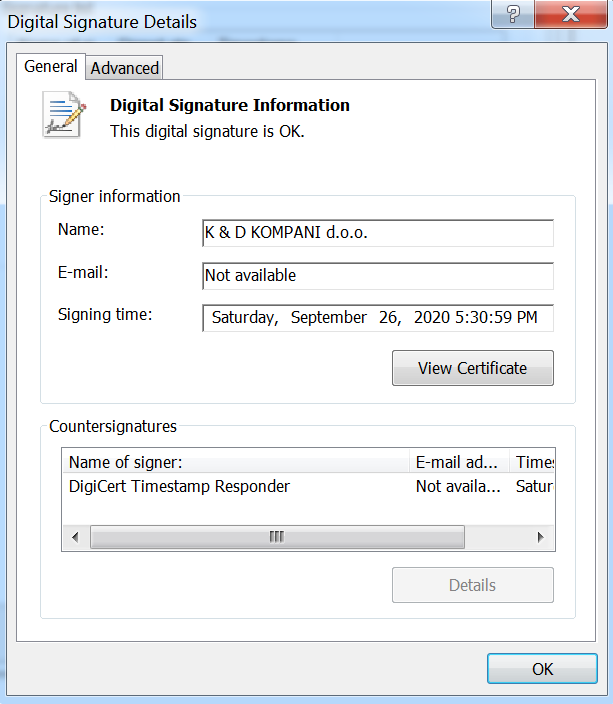

This particular Ryuk sample (f8bc1638ec3b04412f708233e8586e1d91f18f6715d68cba1a491d4a7f457da0) has a signed digital certificate which was explicitly revoked by its issuer.

- Serial Number: 0a 1d c9 9e 4d 52 64 c4 5a 50 90 f9 32 42 a3 0a

- Subject: CN = K & D KOMPANI d.o.o

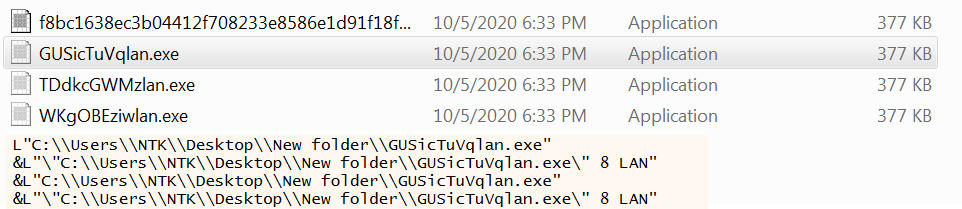

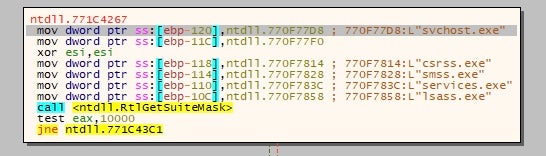

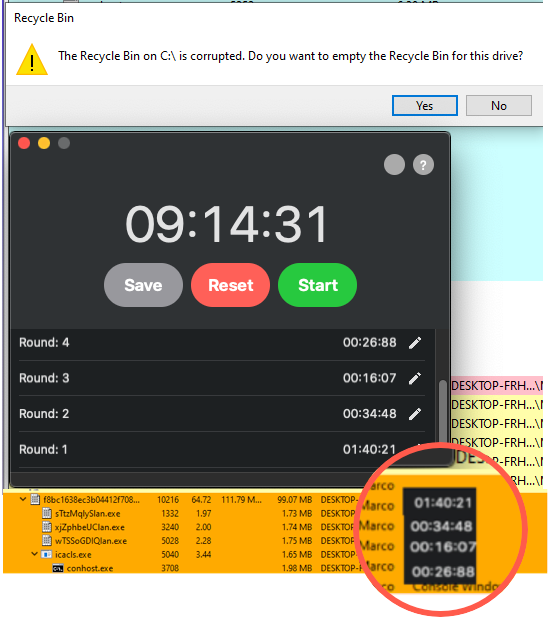

When Ryuk begins executing, it duplicates itself and dumps this copy into the same directory with a randomly generated 8 character name. However, the file name always ends with “…lan.exe”. These duplicate files help to start multiple threads. Ryuk utilizes a list of hardcoded strings to search for and stop specific running processes (Figure 1). It then tries to inject itself into additional processes.

Ryuk next begins executing certain command line tools to achieve some of its devastating effects; in particular, it tries to prevent user recovery by attempting to delete the Volume Shadow copies by leveraging cmd.exe /c 'WMIC.exe shadowcopy delete'. This is followed with a cmd.exe /c 'vssadmin.exe Shadows /all /quiet” and cmd.exe /c 'bcdedit /set {default} recoveryenabled No & bcdedit /set {default}'.

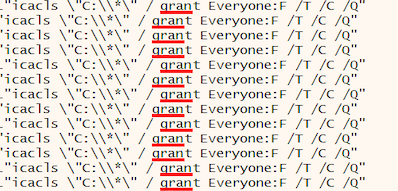

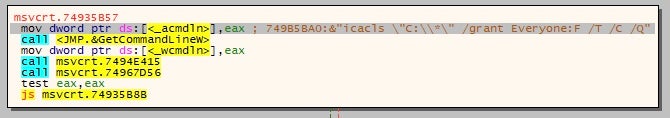

An icacls.exe is created in the Windows WoW directory, which gives the group Everyone full permissions to the drives on the system so that Ryuk has everything it needs to encrypt all drives.

Extracting the Executable from Memory

To avoid detection, the malware uses various evasion techniques like self injection. Ryuk uses this technique by allocating memory in which it writes a PE file. After this, it calls VirtualProtect to change the execution permissions on the section.

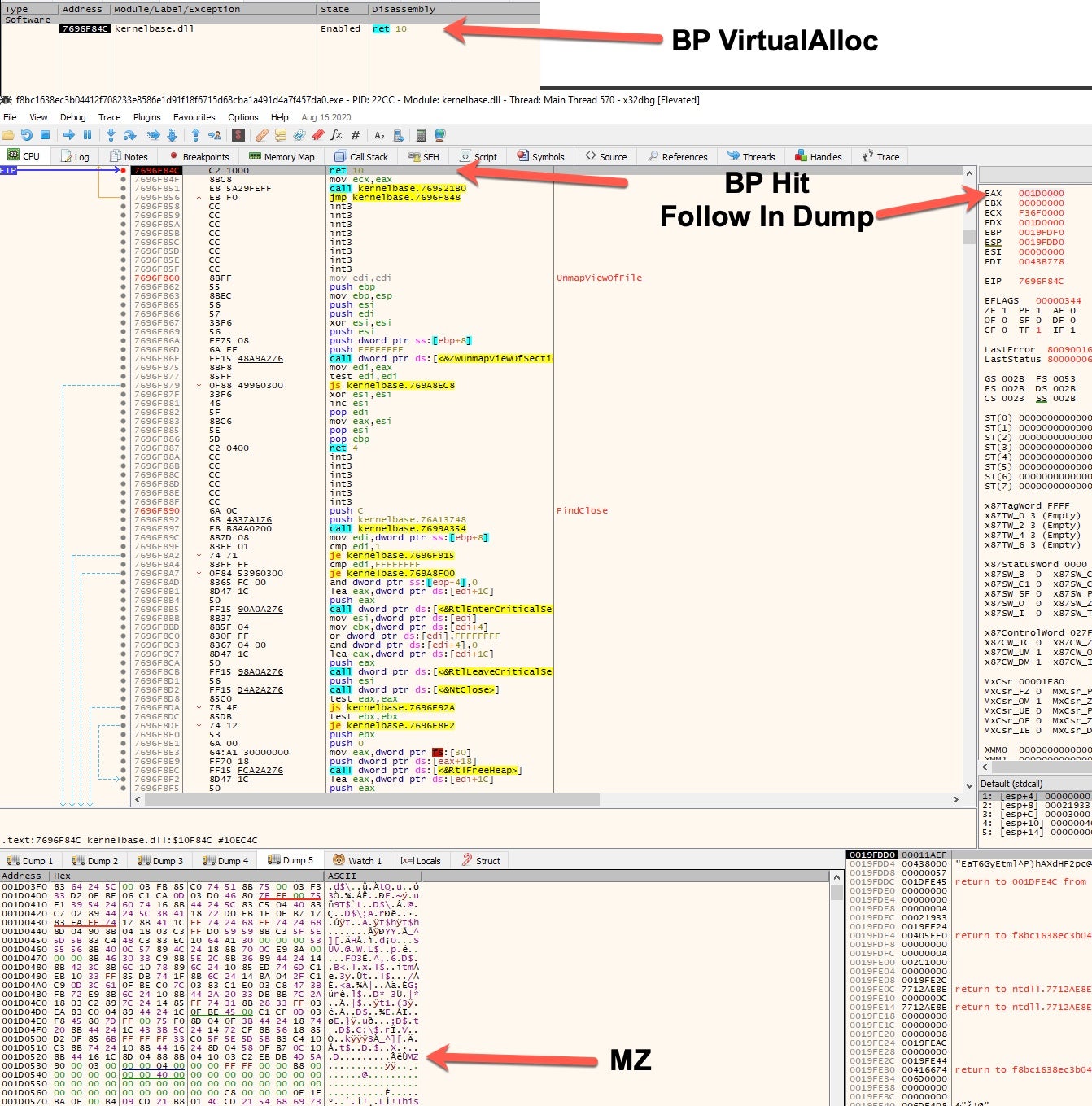

A fast way to extract the executable from memory is to run the binary in a debugger and set a breakpoint at the location of the allocated memory. For this, I use x32dbg, and set a breakpoint on VirtualAlloc. A thing to note is that when setting a breakpoint for VirtualAlloc you should follow the jmp routine into Kernelbase to get the base address of the newly allocated region and set the breakpoint on the return. Once the debugger has run, the breakpoint will hit. Follow the EAX register to the memory dump section to view if the MZ magic is present.

When the process is run, it will hit the breakpoint VirtualAlloc and in the EAX is the newly allocated virtual memory section to begin loading a copy of itself into this section. Following the EAX to the memory dump shows that the memory has been allocated for loading. When continuing the process, the dump window begins to populate with data as it hits the breakpoint that is set several times. Once it is confirmed that the binary has been fully loaded into this section, the binary data can be dumped for inspection.

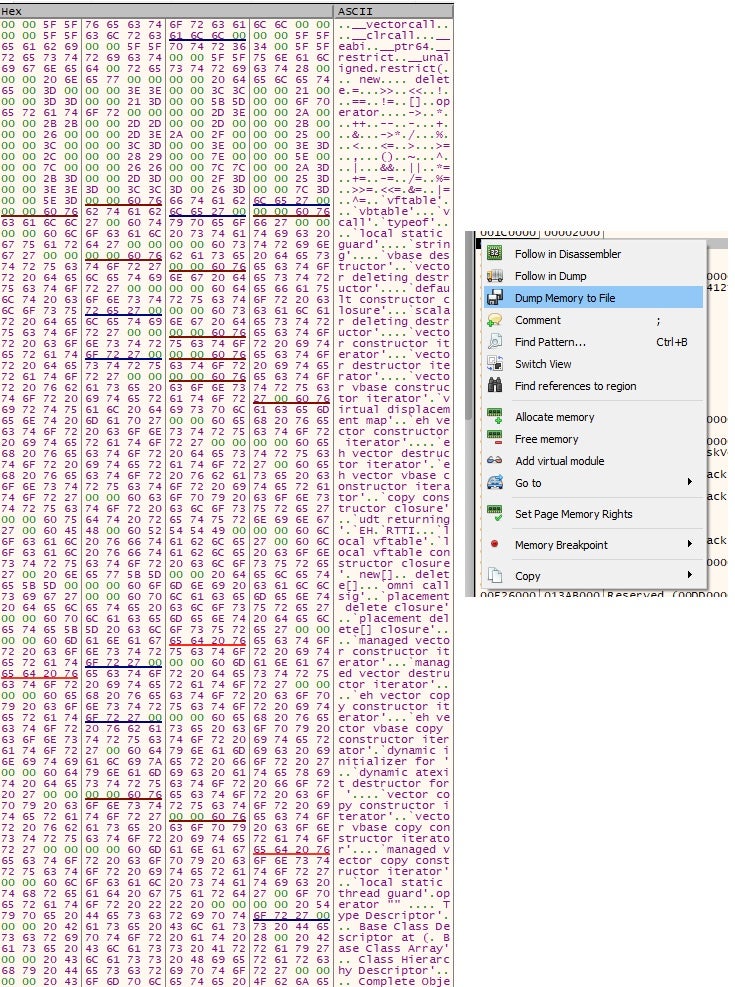

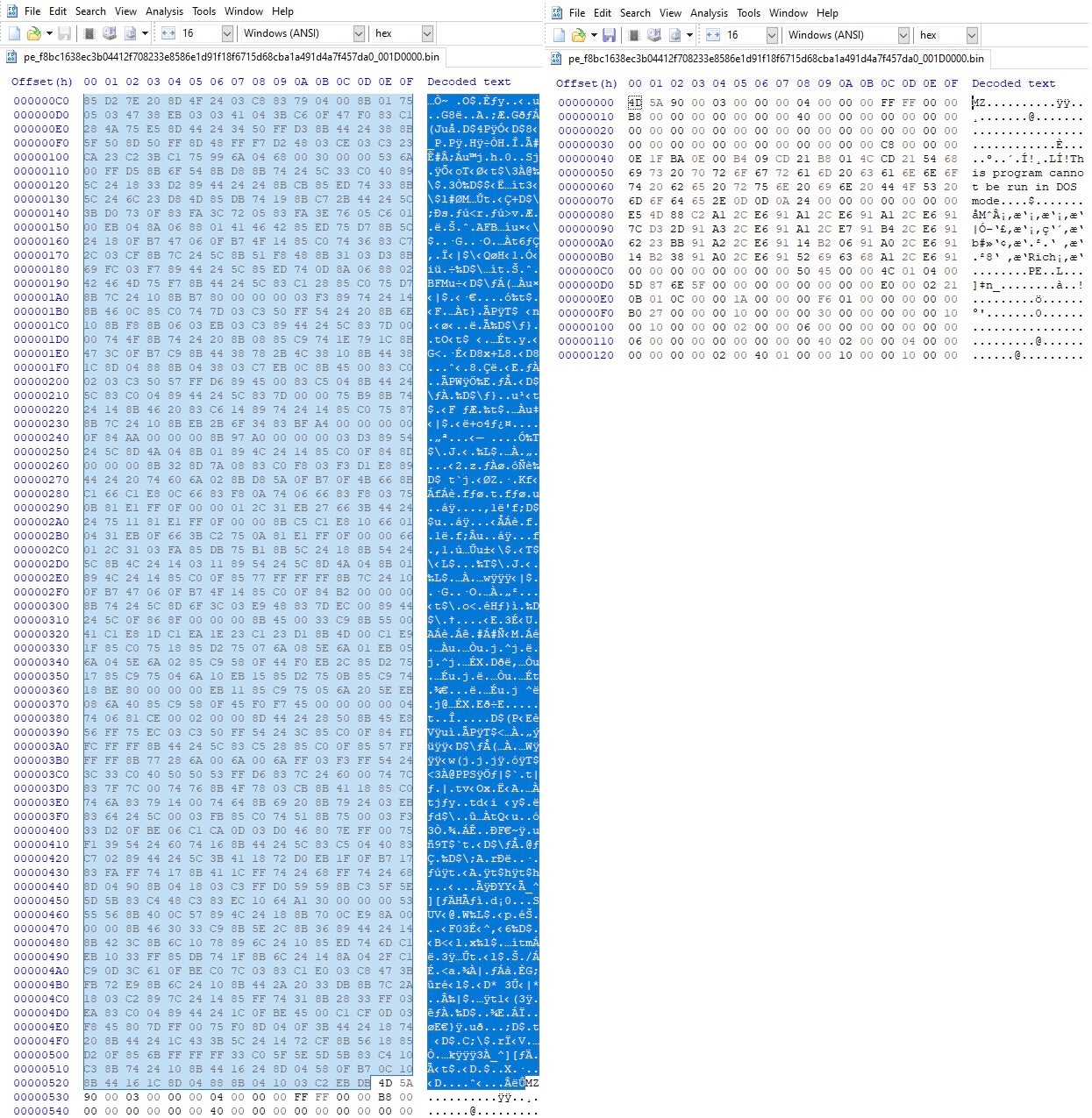

The next step is to right-click on the memory dump and follow the dump in the memory map. This brings you to where the dump has been allocated in memory, and from here you can dump the memory to file. However, as shown in Figure 9, notice that the dumped memory does not have a valid PE header; we have to modify the header so the PE (Figure 10) can work in the tool of your choice.

This particular binary is straightforward to modify. Open up your favorite Hex editor, load the file, highlight everything before the MZ and delete it. Sometimes, just deleting extra bytes will not work if a blob of memory has corrupted magic bytes. In that scenario, you can copy a known good header and add it to the corrupted PE header to make a valid PE.

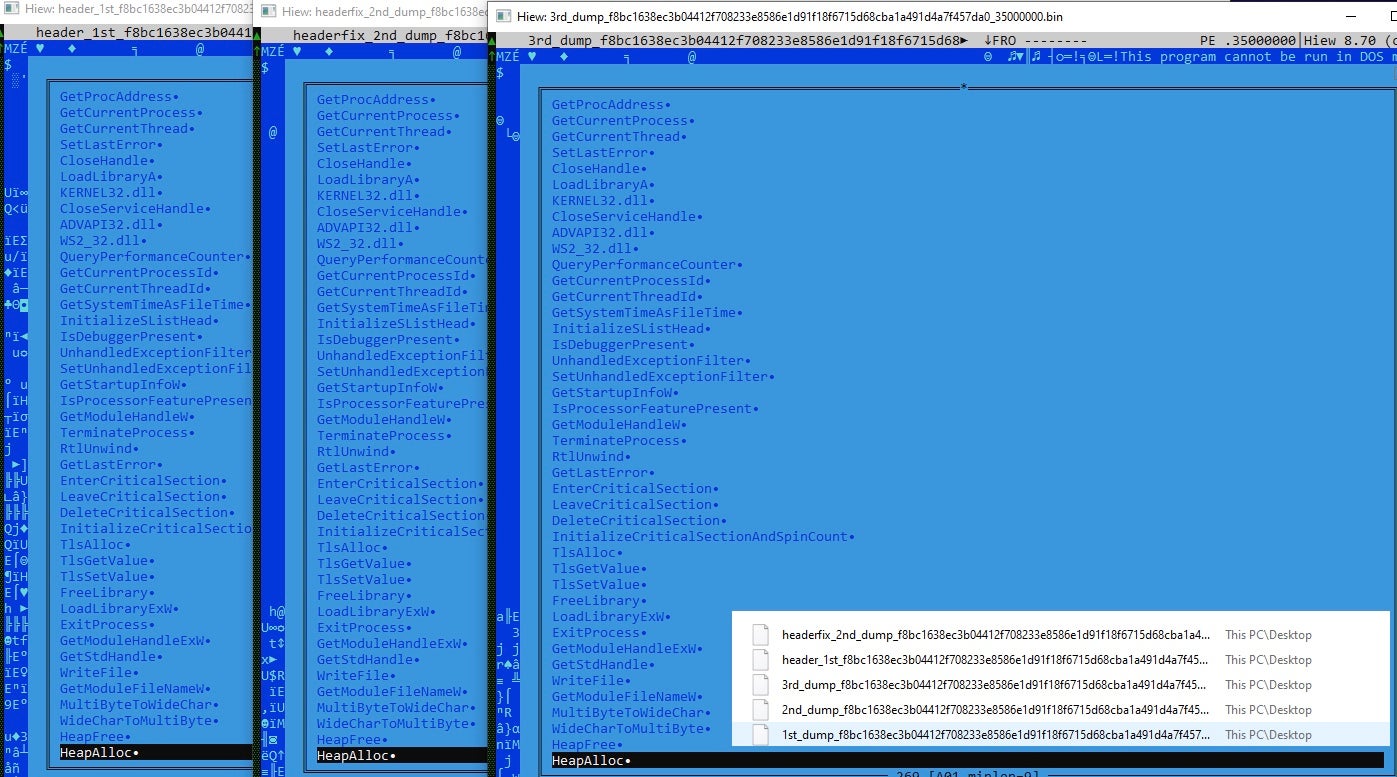

If you follow the process from the beginning, the breakpoint will hit VirtualAlloc additional times. I’ve dumped the memory with the techniques shown above to show why Ryuk’s encryption on a system is so fast:

Conclusion

The FBI has stated that Ryuk Ransomware actors have been paid over 61 million dollars. With Ryuk attacks crippling organizations, this number will soon surpass the 100 million mark if it hasn’t done so already.

However, guarding against the ransomware menace in general and Ryuk in particular is not complicated with the proper protection in place: The techniques used by these cybercriminals are well-understood and relatively simple. The weaknesses they exploit are organizations’ inability to detect and remediate at speed, but this is a problem that can be and has been solved.

Meanwhile, as analysts, it’s important that we keep up with the latest developments and techniques deployed by adversaries. At SentinelOne, we track the ever-changing variants of Ryuk to understand the latest capabilities added to this ransomware family. In this post, we have detailed how Ryuk has evolved to increase its speed of encryption and the methods it uses for evasion. In a future post, we will cover Ryuk’s network layer and the many artifacts collected during our analysis process.

Samples

SHA256: f8bc1638ec3b04412f708233e8586e1d91f18f6715d68cba1a491d4a7f457da0

SHA1: c3fa91438850c88c81c0712204a273e382d8fa7b

SHA256: 7e28426e89e79e20a6d9b1913ca323f112868e597fcaf6b9e073102e73407b47

SHA1: 5767653494d05b3f3f38f1662a63335d09ae6489

MITRE ATT&CK

Command and Scripting Interpreter T1059

Native API T1106

Application Shimming T1546.011

Process Injection T1055

Masquerading T1036

Virtualization/Sandbox Evasion T1497.001

Deobfuscate/ Decode Files T1140

Obfuscated Files or Information T1027

System Time Discovery T1124

Security Software Discovery T1518.001

Process Discovery T1057

File and Directory Discovery T1083

System Information Discovery T1082

Archive Collected Data T1560

Encrypted Channel T1573